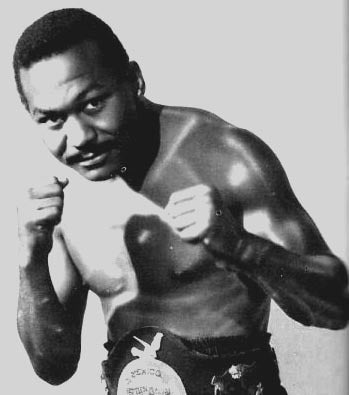

Carmine Basilio (April 2, 1927 – November 7, 2012) better known in the boxing world as Carmen Basilio, was an American professional boxer who had been a two weight class world boxing champion. Some reports have suggested that Basilio changed his name from Carmine to Carmen before he began boxing, to sound more masculine.

Basilio began his professional boxing career by meeting Jimmy Evans on November 24 of 1948 in Binghamton, New York. He knocked Evans out in the third round, and five days later, he beat Bruce Walters in only one round and by the end of 1948 had completed four bouts.

He started 1949 with two draws, against Johnny Cunningham on January 5, and against Jay Perlin 20 days later. Basilio campaigned exclusively inside the state of New York during his first 24 bouts, going 19-3-2 during that span. His first loss was at the hands of Connie Thies, who beat him, by a decision in 6 on May 2 of '49. He and Cunningham had three more fights during that period, with Basilio winning by knockout in two on their second meeting, Cunningham by a decision in eight in their third and Basilio by decision in eight in their fourth.

For fight number 25, it was decided that it was time to campaign out West so Basilio went to New Orleans, where he boxed his next six fights. In his first bout there, he met Gaby Farland, who held him to a draw. He and Farland had a rematch, Basilio winning by a knockout in the first round. He also boxed Guillermo Giminez there twice, first beating him by knockout in eight, and then by knockout in nine. In his last fight before returning home, he lost by a decision in 10 to Eddie Giosa.

In 1952, Basilio went 6-2-1. He beat Jimmy Cousins among others that year, but he lost to Chuck Davey and Billy Graham. The draw he registered that year was against Davey in the first of the two meetings they held that year.

Things began to change for the better for the fighter in 1953. Basilio started winning big fights and soon found his name climbing up the Welterweight division's rankings. Soon, he found himself in his first world title fight, against Cuba's Kid Gavilan for Gavilan's world welterweight championship.

Before fighting against Gavilan, he beat former world light-weight champion Ike Williams, and had two more fights with Graham, avenging his earlier loss to Graham in the second bout between them with a 12 round decision win, and drawing in the third. Basilio lost a 15 round decision to Gavilan and went for a fourth meeting with Cunningham, this time winning by a knockout in four. Then, he and French fighter Pierre Langois began another rivalry, with a 10 round draw in the first bout between the two.

1955 arrived and Basilio began by beating Peter Müller by decision. After that, Basilio was once again the number one challenger, and on June 10 of that year, he received his second world title try, against world Welterweight champion Tony DeMarco. In what has become a favorite fight of classic sports channels such as ESPN, Basilio became world champion by knocking out DeMarco in the 12th round. Basilio had two non title bouts, including a ten round decision win over Gil Turner, before he and DeMarco met again, this time with Basilio as the defending world champion. Their second fight had exactly the same result as their first bout: Basilio won by a knockout in 12.

For his next fight, in 1956, Basilio lost the title in Chicago to Johnny Saxton by a decision in 15. It has always been commented that the reason that Saxton got the nod was because of his ties with the underworld. His manager, Mafiosi, Frank "Blinky" Palermo", was later jailed along with his partner Frankie Carbo for fixing fights. Basilio said of losing his title to the referees' decision, “It was like being robbed in a dark alley.” In an immediate rematch that was fought in Syracuse, Basilio regained the crown with a nine round knockout, and then, in a rubber match, Basilio kept the belt, by a knockout in two.

After that, he went up in weight and challenged aging 37 year old world Middleweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson, in what perhaps may have been his most famous fight. He won the Middleweight championship of the world by beating Robinson in one of the most exciting 15 round decisions in middleweight history, September 23, 1957. The day after, he had to abandon the Welterweight belt, according to boxing laws. In 1957 Basilio won the Hickok Belt as top professional athlete of the year.

In between those fights, he was able to beat Art Aragon, by knockout in eight, and former world Welterweight champion Don Jordan, by decision in ten. His fight with Pender for the title, was also his last fight as a professional boxer.

Following his esteemed career as a fighter, Basilio worked for a time at the Genesee Brewery in Rochester, NY. Basilio, who was also a member of the United States Marine Corps at one point of his life, was able to enjoy his retirement. During the 1970s, his nephew Billy Backus became world's welterweight champion after having a shaky start to his own boxing career, and Basilio declared on the day that Backus became champion, that to him, Billy winning the title was better than when he won it himself.

Basilio was interviewed for an HBO documentary on Sugar Ray Robinson called "The Dark Side Of A Champion". He mentioned that although he respected Robinson's talents in the ring, he did not like him at all as a person. He called him a "son of a bitch" and said he was the most arrogant, unpleasant person that you would ever want to meet.

Sugar Ray Robinson and Carmen Basilio were two of the all-time-greats. They fought twice, the first time on Sept. 23, 1957, at Yankee Stadium in New York, and the second time on March 25, 1958 at Chicago Stadium. Going into the first fight, Robinson, a former welterweight titleholder, was defending the middleweight title he won from Jake LaMotta in 1951. Sugar Ray was 140-5-2 (that’s no typo) going in. Basilio, welterweight champion at the time, was 51-12-7 and had been chomping at the bit to get to Robinson for years. Their first fight was nothing less than amazing. Their second fight no less so. It’s a cliché to say they don’t make ‘em like they used to, but they don’t make ‘em like they used to….

“Carmen put Canastota on the worldwide boxing map and gave the village’s residents a sense of pride that couldn’t be matched anywhere in the world,” said Hall of Fame Executive Director Edward Brophy. “During the 1950s and 1960s Carmen was everyone’s hero. They talked about him in the coffee shops, grocery stores, gas stations and barbershops all the time. And they still talk about him today. He was loved, respected and idolized. His career and memories will last forever in the Village of Canastota.”.

Mike Milmoe, board member of the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the editor and publisher of the Canastota Bee Journal newspaper during Carmen’s fighting days, said, “Carmen was the best known and most famous native son in community history. He gave credibility to the Boxing Hall of Fame in its formative years with his participation and support. When he received the Hickok Award as Pro Athlete of the Year in 1957 after defeating Sugar Ray Robinson for the middleweight championship, he brought worldwide recognition to this community. Wherever he lived or visited his heart was always in Canastota. He was a wonderful individual and our best community ambassador.”.

"Many years ago I remember reading an article about Carmen in Ring magazine. They interviewed a State Trooper who didn't wish to give his name for the record. Pertaining to Carmen he said, "Yeah, I know him. He's a punk, and he's beatable, but you'd better pack a lunch because it's going to take you all day." I also remember his hands were so bad (brittle), they let him down time and time again. He almost walked away from the sport. Of course it's what he did against Tony De Marco and Sugar Ray Robinson that we'll remember him for. 'Concrete' Carmen, you were that boxing rarity: A Champion's Champion. It's time to rest. "

Reference

Carmen Basilio. (2014). Retrieved on April 27, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmen_Basilio.

Sugar Ray Robinson vs. Carmen Basilio I & II. (2014). Retrieved on April 27, 2014, from http://www.boxing.com/sugar_ray_robinson_vs._carmen_basilio_i_ii.html.

The Sweet Science. (2014). Rest in Peace, Carmen Basilio, Toughest Onion Farmer Ever. Retrieved on April 27, 2014, from http://www.thesweetscience.com/news/articles/15530-rest-in-peace-carmen-basilio-toughest-onion-farmer-ever.